This tool has been developed as part of the Inclusive School Communities Project, funded by the National Disability Insurance Agency. The project is led by JFA Purple Orange.

Introduction

This tool was written by Loren Swancutt, Head of Inclusive Schooling at a public high school in Queensland. Loren has successfully led the sustained development and implementation of inclusive school reform in her local school contexts. She has been seconded into Regional coaching roles supporting Principals to advance inclusive education practices. Loren is highly regarded for her innovative work in relation to differentiated teaching practice and inclusive curriculum provisions, a topic she is researching as a doctoral candidate at the Queensland University of Technology.

This tool introduces school leaders to the concept of inclusive education by outlining its authoritative definition, principles and core features. The tool highlights the distinct differences between mainstream and inclusive education, addressing some of the misconceptions and misappropriation, which often confuses and hinders inclusive education reform efforts. The tool contains three handouts what are aimed at providing practical ways that school leaders can reflect on practice, prioritise action, and monitor impact throughout their inclusive school improvement agendas.

Inclusive education is supported by decades of research1 and first gained international recognition in the 1990s through the Salamanca Statement and Framework on Special Needs Education (Salamanca Statement)2. Its principles are present in a number of authoritative legal instruments around the world, including national anti-discrimination legislation in Australia3, and international human rights law4. In 2006, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD) surpassed the Salamanca Statement, replacing its aspirational commitment with a legally binding obligation. The CRPD provides an authoritative framework for thinking about policy and practice reform. Through Article 24: Education, it requires signatories to support the implementation of inclusive education, and to reduce segregation5.

Despite robust research and human rights law supporting the implementation of inclusive education, widespread advancement has been stagnant. The historical lack of a definitive position on what constitutes inclusive education distorted its principles and purpose, and impeded realisation efforts. To combat this, in 2016 General Comment No. 4 (GC4) on Article 246 was constructed to clearly articulate a definition of inclusive education7. The definition has worked to remove previous ambiguity and interpretation.

GC4 not only provides a definition, but also highlights the need for systemic reform to education systems and schools, and urges the discontinuation of parallel systems, which provide special and segregated education provisions. It outlines nine core features of inclusive education that work to ensure all students can access, participate and make progress in education alongside peers in regular school environments and experiences.

Ideas

Definition of Inclusive Education

GC4 authoritatively defines inclusion as:

A process of systemic reform embodying changes and modifications in content, teaching methods, approaches, structures and strategies in education to overcome barriers with a vision serving to provide all students of relevant age range with an equitable and participatory learning experience and environment that best corresponds to their requirements and preferences.8

It goes on to note:

Placing students with disabilities in mainstream classes without appropriate structural changes to, for example, organisation, curriculum and teaching and learning strategies does not constitute inclusion. Furthermore, integration (placing persons with disabilities in mainstream institutions so long as they can adjust to the standardised requirements) does not automatically guarantee the transition from segregation to inclusion.9

Importantly, GC4 identifies provisions that are incompatible with inclusive education by defining exclusion, segregation and integration as:

Exclusion occurs when students are directly or indirectly prevented from or denied access to education in any form.10

Segregation occurs when the education of students with disabilities is provided in separate environments designed or used to respond to a particular or various impairments, in isolation from students without disabilities.11

Integration is a process of placing persons with disabilities in existing mainstream educational institutions, as long as the former can adjust to the standardized requirements of such institutions.12

Core Features of Inclusive Education

GC4 stipulates that the core features of inclusive education are:

1. Whole systems approach

2. Whole educational environment

3. Whole person approach

4. Support teachers

5. Respect for and value of diversity

6. Learning-friendly environment

7. Effective transitions

8. Recognition of partnerships

9. Monitoring

Mainstream vs. Inclusive Education

When considering inclusive education, it is important to note its distinction from the ‘mainstream.’ The terms ‘inclusive’ and ‘mainstream’ are often used interchangeably but are in fact mutually incompatible6. As noted in the GC4 definition, placement in existing educational structures without the necessary changes to ensure equitable access and participation is not inclusive education. Inclusive education transcends mere physical presence in existing general education contexts. It instead requires a recalibration of the thinking and doing associated with all aspects of current education provision. It demands a philosophical commitment that values, acknowledges and expects diversity. It requires learning experiences and environments that are universally designed to be responsive and equitable, and it requires that all students learn and interact together across regular education contexts. These conditions for inclusive education can be summarised via the following formula:

Inclusive Education = Philosophy + Practice + Place

Philosophy: Beliefs, attitudes and principles that underpin school culture.

Practice: Structures, systems, processes, and actions that are enacted across the schooling experience.

Place: Physical proximity, opportunity, access and participation.

Inclusive School Reform

In order for inclusive education to be realised, schools need to engage in reform processes. Inclusive school reform involves the transformation or redesign of current mainstream offerings. Reform efforts are needed to eliminate the deficits that exist in the current and outdated mainstream provision, and to move away from ogranisational systems and structures that are focused on ‘most + some’, to ones that are compatible for ‘everyone’13.

Ultimately, inclusive school reform is about school improvement. School improvement focuses on building and sustaining highly effective schools. That is, leadership, teachers, culture, resources, pedagogy and community all working together to effectively change school practices that lead to improved student outcomes. Inclusive school reform extends the concept of school improvement to ensure that efforts and outcomes are experienced by the entirety of diverse student populations, with all students accessing participating and making progress in their age-equivalent curriculum and regular grade level classrooms. Combining inclusive school reform with school improvement also generates the conditions for the transformation to be prioritised at a whole-school level, and for the change process to be scalable and sustainable.

Actions

A core component of successful inclusive school reform involves considered reflection, prioritisation and implementation of evidence-informed actions, and monitoring of impact. Essentially – Where is the school at in their inclusive school reform journey? What are their strengths and challenges? What are they doing to improve? How do they know it is working?

An inquiry approach is a great way to engage with these questions. It is an enabler of professional learning that impacts permanent change in thinking and behaviour, and it can support teachers to reconcile discrepancies between initial thinking and new ways of working that emerge through examination, collective efficacy, and reflection.

The following handouts have been created to provide schools with practical ways they can engage in reflection, planning, and monitoring of inclusive school reform through an inquiry lens:

Handout 1: Reflecting on strengths and challenges

Handout 2: Prioritising actions and planning for improvement

Handout 3: Monitoring outcomes and impact

It is recommended that school leaders form a collaborative team that encompasses a range of roles and responsibilities from across the school to encourage broad perspective and experience. The team should start by utilising Handout 1 to engage in initial data gathering that can be used to open up further discussion, analysis and lines of inquiry around strengths and challenges.

Once data has been gathered and analysed, the collaborative team should then utilise Handout 2 to inform the development of key priorities and actions for inclusive school improvement. A range of prompts and tools are outlined to help inform this process.

Finally, Handout 3 can be used by the collaborative team on an ongoing basis to inform the monitoring and review of key priorities and actions. It provides prompts that can be used to review the fidelity and impact of improvement efforts across time.

Handout 1: Reflecting on Strengths and Challenges

Where is the school at in their inclusive school reform journey? What are their strengths and challenges?

An important first step in an inquiry approach is to assess the current reality. Performing this initial reflection and assessment will highlight areas of strength and challenge and will provide an overall picture of the current educational experiences and outcomes of all students in the school.

When engaging in reflection and assessment, it is important for collaborative teams and vested individuals to have a clear understanding of the authoritative definition of inclusive education. Without a clear line of sight regarding what inclusive education is and looks likes, the gathering and interpretation of data can occur in a manner which does not serve the desired purpose.

Reflecting on strengths and challenges through the inclusive school reform lens…

Inclusive Education = Philosophy + Practice + Place

Philosophy

• What is the culture of the school?

• What are its values?

• What are its shared beliefs and understandings?

Practice

• What organizational structures are present?

• What systems and processes are in place?

• What pedagogical approaches and instructional practices are implemented?

• How is resourcing used and maximized?

• How is collaboration facilitated?

• How is self/collective efficacy increased?

• What impact do all of these decisions and ways of working have?

Place

• Where do students learn?

• What experiences do they engage in?

• What opportunities are available and for whom? Who do students interact with?

• Who do staff interact with?

Ways of Gathering Data

Both qualitative and quantitative data sources support schools in gathering and analysing informed responses to the reflections posed above. Examples of ways such data can be sourced are explored in the table below.

|

Source / Process |

Description |

|

Student Outcomes |

Analysing student outcomes provides opportunity to look for patterns and trends, identify areas of success, and determine any areas of inequity. It shifts the focus from being solely about student access and participation, to one that is also centered on progress and outcomes. Performance indicators around academic achievement, school disciplinary actions, attendance, and senior school attainment can all be analysed. Analysis can occur in relation to overall performance of student cohorts, and comparatively between students with and without disability or other forms of student diversity and demographics. Utilising data systems that are often part of school management software, and/or developing an excel spreadsheet can support the collation and analysis of data. |

|

Map It Out |

Use a school map to visually represent student access and participation, and human and physical resource use. |

|

Student Consultation |

Adults can often assume that they know what is going on for learners. However, when students are approached with genuine curiosity, they can provide a more contextual and authentic perspective. Inclusive education is after all about student experience. Ideas for gathering student input: For support with engaging in accessible consultation processes with students, access a practice guide here: https://research.qut.edu.au/c4ie/wp-content/uploads/sites/281/2020/08/Practice-Guide-Student-Consultation.pdf |

|

Teacher Consultation |

Teacher consultation can be used to determine beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, confidence, and capability. Having data around current levels of capacity can inform the prioritisation of professional learning and work relating to the development of culture and collective efficacy. Ideas for gathering teacher input: |

|

Self-assessment Tools |

There are a number of inclusive education self-assessment tools that detail key expectations and practices relating to successful implementation. The tools are best completed with a range of perspectives from across the school community. Recommended tools include: |

Further discussion regarding the practical implementation of the data gathering methods can be viewed here: https://vimeo.com/436285630

Analysis

Some simple ways to commence analysis of your initial reflection and assessment are:

• SWOT Analysis – identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats

• Fishbone Diagram – looking at what effects are occurring and backward mapping to consider causes and contributions

• PMI – identifying positives, minuses, and interesting points of thought and practice

• Head, Heart & Feet – What have I learnt form the data? How do I feel about the data? What action do I want to take as a result of the data?

Handout 2: Prioritising Actions and Planning for Improvement

What are they doing to improve?

With some informed perspective from the initial data gathering and analysis phase, the focus can shift to prioritising actions and planning for improvement. This process involves identifying student learning and engagement needs, identifying gaps in teacher confidence and capability, and determining actions to address the challenges of practice.

A collaborative team should work together to:

• Ask questions and seek further clarification

◦ What can we celebrate?

◦ What requires further exploration?

◦ What concerns us?

• Develop theories of action based on a shared vision that upholds the intent of inclusive education

◦ What concerns are of greatest priority?

◦ What current systems, process and practices could be impacting and influencing this?

◦ Why is it imperative to address this priority?

• Determine action steps that consider professional learning, collective understanding and evidence-based decisions and strategies

◦ What improvement strategies could be implemented?

◦ What would be the anticipated change?

◦ What does the change look like?

◦ What capability is needed?

◦ Do we have the capability? How can we get it?

• Identify roles, responsibilities, and fidelity measures to ensure ongoing monitoring and feedback

◦ Who will lead this work?

◦ Who will contribute to this work?

◦ What does successful implementation look like?

◦ How will implementation be monitored and reviewed?

Prioritising and planning through the inclusive school reform lens…

Inclusive Education = Philosophy + Practice + Place

Philosophy

• Is there a clear and public vision for inclusive education?

• Has bias and discrimination in language and actions been identified and addressed?

• Is disability seen as diversity and not as deficit?

• Do all staff understand the social model of disability?

• Do all staff understanding the definition of inclusive education in principle and practice?

• Do all staff believe inclusive education benefits everyone?

• Are all staff aware of their legal obligations relating to the Disability Standards for Education?

• Are all staff willing to reflect and change to improve practice for all students?

Practice

• Do all teachers have a shared ownership of all students?

• Are there high expectations for students with disability?

• Are strengths-based perspectives and strategies used?

• Are universal design principles and differentiation used to ensure learning is accessible and engaging for all students?

• Do teachers and support services collaboratively plan and teach together?

• Do teachers understand standards-based curriculum and the flexibility of its design?

• Do all teachers understand the purpose of assessment and provide multiple means for students to demonstrate learning?

• Are all students supported to access, participate in, and make progress through age-equivalent content?

• Is the use of teacher assistants carefully consider and effectively utilized?

• Is collaborative instructional planning a priority?

Place

• Do all students access regular grade level classrooms for all learning experiences?

• Are students with a disability proportionally placed across all classes in a grade level?

• Are physical environments designed to be accessible and functional for all students?

• Are extra-curricular activities purposefully designed to ensure equitable access and participation for all students?

Frameworks

The following frameworks provide processes for directing meaningful focus, establishing clear and shared visions, and planning appropriate action:

Design Thinking

Design thinking is an approach to learning, collaboration and problem solving. It is a structured framework that supports the identification of challenges, gathering of data and information, generating possible solutions, prioritising actions, and implementing solutions.

Find out more at: https://designthinkingforeducators.com/

GROWTH Framework

The GROWTH Framework provides a simple but effect scaffold to goal attainment. It guides clearly defined actions that are focused on future improvement and considers factors that influence the sustainability of new practices.

Find out more here: https://www.growthcoaching.com.au/about/growth-approach

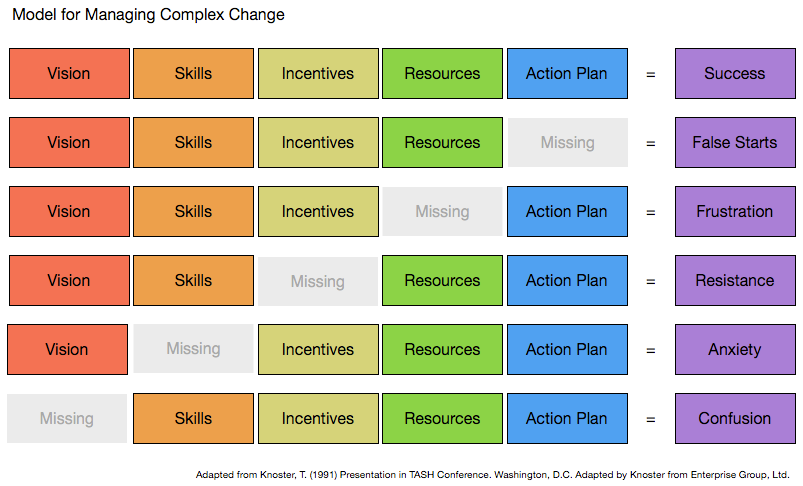

Knoster Model for Managing Complex Change

The Knoster Model for Managing Complex Change is a useful framework in ensuring the elements of effective change have been accounted for. It aims to prevent the confusion, resistance, frustration, anxiety, and false starts that can occur when engaging in change processes.

Handout 3: Monitoring Outcomes and Impact

How do they know it is working?

Monitoring the outcomes and impact of decisions and actions is essential to ensuring efforts are effective. Data gathering and analysis should occur at regular intervals to monitor the frequency and fidelity of actions, and to determine progress toward equitable educational experiences and outcomes for students. Evidence from the monitoring process should be used to determine next steps in implementation – this may result in reconsidering actions, seeking further data or capability, or elevating practice to scale and sustain success.

Data gathering and analysis processes should be built into action plans to support transparency and accountability. Time frames should be clearly articulated and adhered to. During early phases of implementation these timeframes should occur more frequently (every 2-3 weeks) to support the establishment of the desired actions and practices. Once data indicates that practices are embedded, timeframes for monitoring and review can be extended (once per month/once per Term/once per Semester).

The collaborative team should meet to consider:

• How are we going?

• How do we know?

• What are out next steps?

Monitoring outcomes and impact through the inclusive school reform lens…

Inclusive Education = Philosophy + Practice + Place

Philosophy

• How have the beliefs, attitudes and principles of the school progressed?

• How are these reflected in language and actions? Is the vision clear, written and well known?

• Are all students respected and valued?

Practice

• In what has been done, who has been missed?

• What does the data indicate about effectiveness?

• Is there a high level of frequency and fidelity of action?

• How are successful actions being scaled and sustained?

Place

• Is there a possibility for increasing/improving opportunity?

The ways of gathering data suggested in Handout 1 are also useful for ongoing monitoring of outcomes and impact. Completing the same or similar measures at intervals will help to highlight and represent the advancement of inclusive reform across time. The journey can be shared and celebrated with the school community.

An inquiry approach is cyclical. It is designed to be informed by ongoing analysis of experience and impact. Priorities and actions should be regularly reflected upon and assessed to ensure that efforts are informed and impactful. The process of inclusive school reform is a continuous journey of improvement, not a destination.

More Information

Zoom Webinar Recording – Scan and Assess https://vimeo.com/436285630

Swancutt, L., Medhurst, M., Poed, S., & Walker, P. (2020). Making adjustments to curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. In L.J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive Education for the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 55-78). Allen & Unwin.

School Inclusion – From Theory to Practice https://school-inclusion.com/

Acknowledgement

This tool was written by Loren Swancutt, Head of Inclusive Schooling at a State High School in Queensland. In writing this tool, Loren draws on her 11 years teaching experience across both primary and secondary school settings, her experience as a school leader and Regional coach, and her role as the National Convenor of the School Inclusion Network for Educators. Loren is highly regarded for her innovative work in relation to differentiated teaching practice and inclusive curriculum provisions, a topic she is researching as a doctoral candidate at the Queensland University of Technology. https://school-inclusion.com/

References

1 de Bruin, K. (2020). Does inclusion work? In L.J. Graham (Ed.), Inclusive Education for the 21st Century: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 55-78). Allen & Unwin.

2 UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. UNESCO.

3 Productivity Commission. (2003). Review of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992. Commonwealth of Australia.

4 United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations.

5 United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. United Nations.

6 United Nations. (2016). General Comment No. 4, Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education. Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.